Is a color merely a color? Or does it carry the memory of a nation, the voice of a culture, and the codes of an era?

By Prof. Dr. Recep Karadağ

Cultural Heritage Preservation and Natural Dyes Project

İstanbul Aydın University

Turkish Cultural Foundation DATU

Some colors that have survived the depths of history represent not only aesthetic traces but also cultural identity, technological knowledge, and economic value. One such color is Turkish Red, known in Western literature as Turkish Red. This extraordinary color, shaped by the artisans of the Ottoman Empire, emerged in the 16th century in centers like Izmir, Bursa, Edirne, Balikesir, and Ankara. It mesmerized Europe, contributed to the Industrial Revolution, and was finally revived through modem scientific methods.

A Cultural Heritage Turkish Red is not just a dye; it is a cultural production model based on harmony with nature and skilled craftsmanship. The main materials used in producing the dye include the roots of madder (Rubia tinctorum L.), native to Anatolia, gall oak (Quercus infectoria), and a traditionally prepared Turkish Red oil. This multi-layered and unique technique involves a complex dyeing process comprising exactly 38 steps. Chemically, the dye is based on a complex structure formed by the combination of the alizarin dyestuff found in the madder roots and calcium and aluminum ions (Calcium-Alizarin- Aluminum complex). This structure is a striking example of how natural colors can be transformed using scientific methods.

Although some claims link this technique's origins to India, this assertion is scientifically invalid. The Munjest (Rubia cordifolia) plant, native to India, does not contain alizarin dye stuff and uses different substances for red dyeing. In contrast, Turkish Red is based on alizarin and obtained from madder (Rubia tinctorum), confirming its origin in Ottoman territories.

Madder (Rubia tinctorum L.) dye plant

Gall oak (Quercus infectoria)

"One of the most influential factors in the Industrial Revolution was the rise of the cotton industry."

This technique, kept secret for centuries, was transferred to Europe in 1746 when French industrialists brought two Ottoman artisans, d'Haristoy and Goudard, to France. The process began with dye workshops established in the Languedoc region and soon turned into full- blown industrial espionage. Countries like England and the Netherlands sent agents to learn the technique.

In 1784, the Borelle brothers introduced a new method to the Manchester Trade Committee. In 1786, the British Parliament officially protected this method. In Scotland, under George Mackintosh and David Dale, the technique was industrialized. Around the same time, Daniel Koechlin founded Europe's first large scale calico printing factory in Mu/house.

Reports from French Consul Felix Beaujour between 1794-1800 noted that the town of Ampelakia in Ottoman territory had prospered economically due to Turkish Red production. However, as European states improved and spread the technology, the Ottoman Empire quickly lost its informational and production superiority.

One of history's ironies is that the Ottomans, who had developed this unique dyeing technique, eventually found themselves importing fabrics dyed in Turkey Red from China and Indonesia. Either the knowledge was completely forgotten, or its export was deliberately restricted. Ultimately, Turkey Red became a legacy that spread from local to global, yet could not be claimed by its originator.

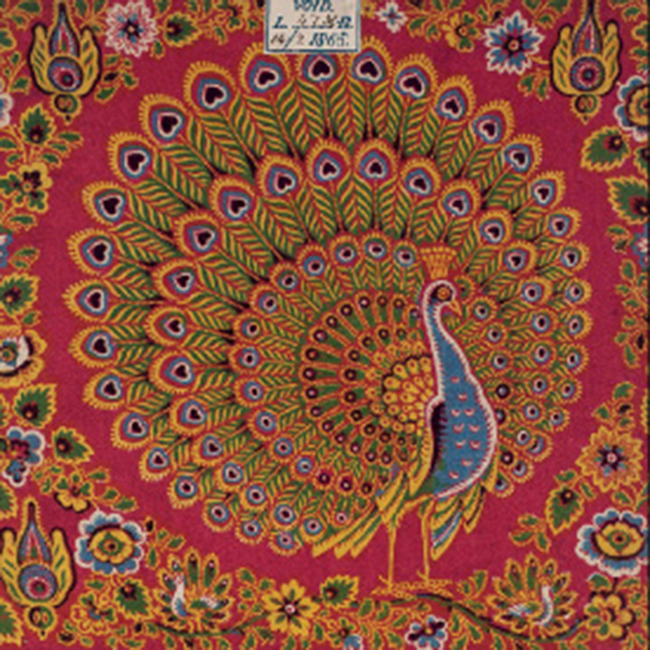

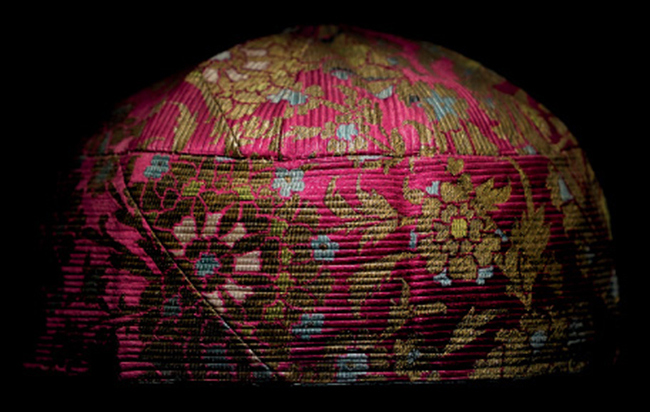

Kaftan dyed with Turkish Red (Topkapi Palace Museum)

Kaftan dyed with Turkish Red (Topkapi Palace Museum)

Many respected European universities launched doctoral and postdoctoral studies to unlock the secrets of Turkish Red. Among the most significant were studies at the University of Glasgow. One key project was J.H. Wertz's doctoral research: "Authenticating Turkey Red Textiles through Material Investigations by FTIR and UHPLC". Another was the book by S. Nenadic and S. Tuckett: "Colouring the Nation: The Turkish Red Printed Cotton Industry in Scotland, c.1840- 1940". Although the exact formula remains unsolved, these studies yielded critical insights.

Samples from museums and archives were subjected to advanced chemical analysis at DATU (Cultural Heritage and Natural Dyes Laboratory).

Numerous experimental dyeings were conducted. These efforts led to the full rediscovery of the historical Turkish Red dyeing formula. Its chemical structure was scientifically confirmed and officially patented in 2017 under number TR 2015 00638 B.

This fascinating color was revived in 2017 through scientific research initiated by the Turkish Cultural Foundation and supported by Dr. Yalçın Ayaslı. As part of the project: Fabric samples taken from the Topkapı Palace Museum and the Military Museum in Harbiye were analyzed. Nineteenth-century catalogs of Turkish Red-dyed fabrics from the Glasgow University Archive were studied.

Today, Turkish Red is not only a historical color but also an exemplary value in terms of sustainable production, natural chemistry, and cultural identity:

This color touches not only fabrics but also Turkey's cultural memory, industrial history, and environmentally harmonious future.